The historian Christopher Dawson (1889-1970) has much to say to us as we witness the extreme secularisation of our once Christian culture. He understood from his extensive studies of the history of cultures that religion played a vital role in the rise of civilisations. He also was convinced that a decline of a religious underpinning of a culture will hasten its demise.

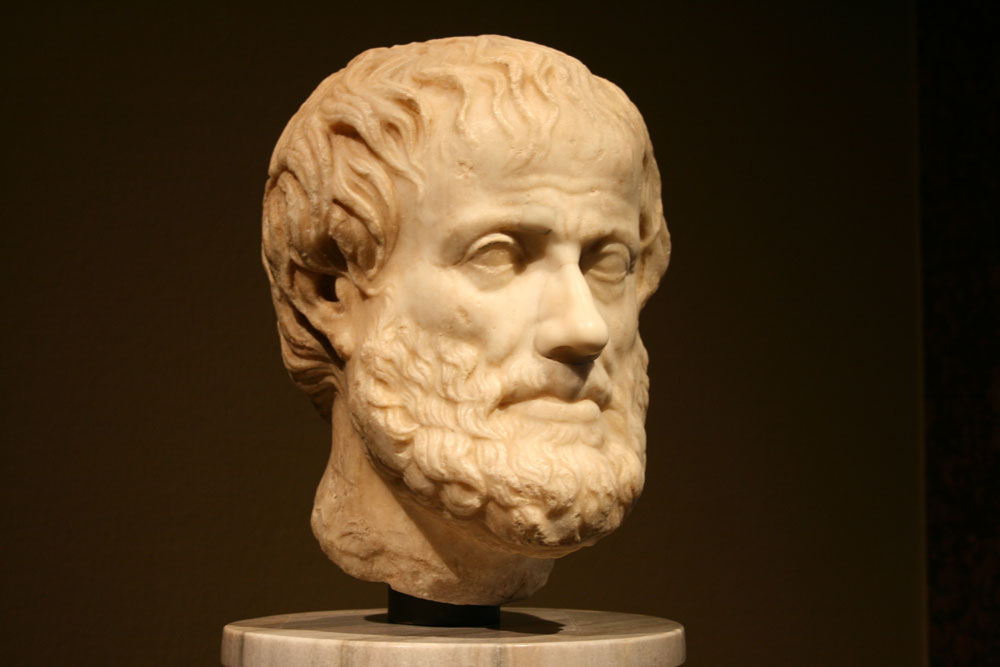

Image: Wikimedia Commons

In his book, Progress and Religion, Dawson makes the claim, “Every living culture must possess some spiritual dynamic, which provides the energy necessary for that sustained social effort which is civilization. Normally this dynamic is supplied by religion, but in exceptional circumstances the religious impulse may disguise itself under philosophical or political forms”.

Over the span of human history Dawson recognised that there was a strong correlation between religion and culture. He commented, “Every culture is like a plant. It must have its roots in the earth, and for sunlight it needs to be open to the spiritual. At the present moment we are busy cutting its roots and shutting out all light from above.”

A study of the history of humanity reveals that the great civilisations and the moral structures that underpinned them found their stability in a reference point beyond themselves. They all had some form of transcendent foundation grounded in the belief in a world beyond the present. Whether it be the pagan gods of Greece or Rome or the articulation of Christian virtue inspired by Sacred Scripture, societies have fashioned moral imperatives based on some form of transcendent order. The moral structures have, in their turn, defined the cultures and have been a point of social cohesion.

However, Western societies whose foundation has been based in Christianity, have now entered a stage of abandoning such a reference point.

Replacing the Christian worldview there is now an emphasis on individual subjective feelings.

Having largely abandoned the Christian vision of human life, society now tends to be directed by popular social movements, which are based more in emotion than reason and evidence. The rise of extreme climate activism and Woke ideology with its promotion of ‘diversity and inclusivity’ are examples of social activism devoid of a transcendent foundation or purpose.

Such causes have become of paramount importance in our society and are so compelling to the social elites that they are forcibly imposed through our education systems, the corporate sector and legislation. Any resistance to the dominant cultural mindset is punished through being ‘cancelled’ or having your employment threatened. These movements, however, are quite fluid and will tend to shift and change as society becomes caught up with new and different issues.

What is, in fact, occurring is that moral thinking has been turned inward. It has not only become untethered from an orientation towards the transcendent, but has also discarded the need for a sound rational base. It is now grounded in the personal feelings an individual has about ethical issues. The moral order has become highly subjectivised.

In times past ethical codes were based in an order defined by the existence of a divine or transcendent reality. They acknowledged the existence of a higher objective or transcendent moral law, often referred to as the natural law, which provided guidance as to how human beings should act in order to flourish or fulfil their nature.

Aristotle taught that ethical beliefs provided a path for human flourishing. This approach understood that there was a higher purpose to human life than the mere satisfaction of desire. Such ethical systems proposed the pursuit of virtue as a central moral ideal.

It is through the development of the virtues that human beings are more easily able to do the right and good thing.

This was at the heart of Aristotelian ethics.

Christian moral teaching has its source in Divine Revelation expressed in the Sacred Scriptures. It draws, in particular, on the Ten Commandments and the moral teachings of Jesus. However, the Catholic Church teaches that we can come to understand the Divine moral law not just through divine revelation but also through what is called the Natural Law, which involves the use of human reason. St Thomas Aquinas was central to the development of natural law thinking, synthesising the importance insights of Aristotle with those of the Christian tradition, in particular the work of St Augustine.

Essentially the Natural Law is the participation in the Divine law through our use of reason. Through the Natural Law we can discern the primary moral precept that good is to be done and evil avoided, reflecting on human inclination we can then identify secondary precepts, which involve goods such as ‘life’, ‘human reproduction’, ‘education’ etc, and the promotion and protection of these goods. These moral precepts of the natural law are not limited by culture or custom. They belonged to all of humanity because all people were created by a wise and provident Creator.

Our society now has large numbers of people who do not believe in the existence of God or any transcendent reality and so we are moving from a transcendent frame of reference to an immanent frame of reference. Once the society no longer acknowledges the transcendent order as providing an objective basis for morality, anything becomes, in principle, morally acceptable and a properly ordered civilised society is no longer possible.

Once a society no longer recognises and respects the existence of the objective moral law, there is only the law of the mob or the strongest and most powerful, and we can only move along the path towards societal collapse.

A number of social commentators have described this process. They have described it in various ways. They speak of the emergence of the ‘imperial self’, or the ‘expressive self’.

One such commentator is Carl Truman who, in his book, Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, speaks of a shift from a world having a given order and meaning to a worldview in which meaning and purpose is created by the individual.

Drawing on the thought of Phillip Rieff he describes three types of worlds. The first was the pagan world with moral codes based on myths. The second world is where moral outlook is based on belief in a transcendent god. The third world has a moral outlook which is devoid of a transcendent element and so is based on nothing beyond the individual human person. This third worldview becomes an ‘anti-culture’ as it sees moral frameworks as oppressive and restrictive of human freedom. It readily dismisses the old moral values as impotent and not a little ridiculous.

Truman maps out a path that humanity has taken as it has distanced itself from the Christian vision of life. He describes the emergence of the “psychological self” which he traces back to the Enlightenment of the 18th century, citing among others, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) who said, ‘all I need to do … is to look inside myself’. Truman describes the ‘plastic self’ where a person considers that they can make and re-make themselves as they wish.

With these changes in self-understanding, so the way of moral thinking has changed.

For the majority, ethics is now a function of feeling, devoid of rational thought.

Such an approach is based in personal subjective preference alone. Alasdair MacIntyre, in After Virtue, describes this approach to ethics as emotivism. What is viewed as morally good is simply what ‘I feel’ is good. The goal of moral choice is seen as self-actualisation or self-expression. Such patterns of thinking can become so distorted that they deny evident biological reality, as we see in the transgender movement.

When moral thinking becomes subjective, an immediate effect is that moral living no longer has a communitarian dimension. Society is fractured into individual preferences. The notion of the common good evaporates. When this occurs we are in fact entering into an era of anti-culture. Moral debate in contemporary society is difficult because people have positions which are either transcendent or immanentist and there is no common ground upon which debate can be pursued. There is no longer a consensus on what constitutes the proper basis for morality. This situation increasingly constitutes an existential threat to our society.

Without the recognition of a higher objective moral law, which we did not create, there can only ultimately be the rule of the strong over the weak, directed by nothing else but the subjective ‘feelings’ of the majority. This is a truly frightening proposition.

Comments